Personalized learning. Project-based learning. Deeper learning. What do these words mean? I thought to myself as I nodded my head in my onboarding meeting, silently praying that my new supervisor wouldn’t suddenly realize she had made a mistake in hiring me. The year was 2016, and I was in Washington, D.C., working to support a national initiative advancing educational equity through innovative education policy reform. I was just beginning my career in education, and already I was swimming in a sea of policy terms and buzzwords that didn’t quite make sense to me.

Isn’t personalized learning just good teaching?

How can competency-based education prepare K-12 students for post-secondary education when most colleges and universities still use traditional grading systems?

What’s the deal with social and emotional learning? Why is it spelled differently (i.e., “socioemotional”) in some publications, but not others? And how do you teach it?

Over the next three years, I would learn more about these concepts by attending webinars, facilitating convenings, and meeting with students, teachers, and school leaders engaged in transformative teaching and learning experiences across the United States.

In Winooski, Vermont, I watched elementary students explain how they addressed a local need by cultivating a community garden through a project-based learning initiative.

In San Diego, California, I listened as a student metaphorically stood on the shoulders of Tupac Shakur, Kendrick Lamar, and other West Coast legends by rapping and performing an original song before dozens of people as part of a deeper learning project.

I witnessed the social and emotional intelligence on display by students in Denver, Colorado, Louisville, Kentucky, and beyond as they shared their career aspirations and how personalized learning was helping them pursue those pathways.

It was a beautiful thing.

And yet, I couldn’t help but notice something – or rather, someone – was missing.

Harvard Professor Jal Mehta noticed, too. In 2014, he penned the Education Week op-ed titled “Deeper Learning Has a Race Problem” (Mehta, 2014). And while Mehta’s focus at the time was on a different innovative education policy, his statement still holds true for SEL policies, practices, and programs today.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) is a Chicago-based organization that has contributed to the advancement of social and emotional learning since the mid-1990s. CASEL defines social and emotional learning (SEL) as:

The process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions (CASEL, n.d., para. 1).

CASEL frames SEL development through its five core competencies: self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision making, relationship skills, and social awareness (CASEL, 2020).

Self-awareness is defined as the ability to identify how one’s emotions, thoughts, and values shape how they show up in different contexts, such as whether a person has the self-efficacy or confidence to take on a given task.

Self-management takes self-awareness a step further by characterizing a person’s ability to employ skills and strategies (such as planning, organization, self-discipline, and stress management) to manage their emotions in pursuit of their goals.

Social awareness concerns the ability to understand and emotionally connect with others, particularly those with whom the socially aware person does not look like or share similar experiences.

Relationship skills, as the name implies, take social awareness a step further by actively working to initiate and maintain positive relationships through understanding, teamwork, conflict resolution, and cultural responsiveness. As such, the relationship between self-awareness and self-management is analogous to that between social awareness and relationship skills: same principles, but with different objectives and intended outcomes.

Responsible decision-making, then, cuts across all four of the previous core competencies in that it reflects one’s ability to evaluate the benefits and risks of given actions on oneself and others and then act accordingly.

SEL programs and policies have little to no chance of advancing educational equity if they avoid issues of race (Attaya & Hilliard, 2023; Cipriano et al., 2025). In their review, Attaya & Hilliard argue for integrating critical race theory (CRT) into existing SEL programs, particularly if the goal of such programs is to prepare students for the future education, work, and social contexts in which they may find themselves. They write:

Students, especially Black, Indigenous, and other students of color, are explicitly harmed by [SEL] programming that ignores the historical and current implications of racial inequity and systemic injustice. All students are done a disservice by SEL programming that does not equip them to navigate the complex sociopolitical issues they experience every day.

Scholars such as Ebony McGee, David Stovall, and Shawn Ginwright agree, calling for education reform that centers identity affirmation and healing (McGee & Stovall, 2015; Ginwright, 2010).

Yes! And what does this look like?

In 2007, Rich Milner introduced a framework to guide education researchers in examining racial and cultural biases and tensions in themselves and others, as a means of fortifying the research process (Milner, 2007). My researcher positionality is rooted in my K-12 educational experiences in Wilson, NC, where I noticed that students who looked like me had the potential to excel in the same academically gifted classes that I was taking, but were barred from doing so by adults who deemed them academically and socially deficient.

Students in my community who were problematically labeled “at-risk” were intellectually gifted in ways that traditional education systems didn’t care to measure. For example, one student who was chronically absent from school once invited me over to his house to play Madden. Because I was familiar with the game and had fallen for the meritocracy myth, I mistakenly assumed I could out-strategize, outthink, and defeat him. My hypothesis was incorrect. Not only did I lose by multiple touchdowns, but he also casually explained to me why his strategy was superior to mine as he beat me.

Another student who was on the verge of being pushed out of school for academic and behavioral reasons was perceived differently in the community. Not only was he a prolific lyricist, able to freestyle rhythmically and coherently “off the dome,” but he also protected me and other students from being bullied on the school bus.

These experiences led me to recognize that traditional schooling systems don’t work for all students, and that students “at the margins” of such systems have much to offer in terms of critical thinking, collaboration, and other social and emotional skills.

So then, the question becomes, how do we make schooling work for those students, too?

I offer that one way we can do so is by integrating cultural phenomena – such as games and hip-hop music – into classrooms and school settings as pedagogical tools. Doing so would affirm students’ identities, make lessons more engaging and meaningful, and prepare students for careers better attuned to their interests. This would be especially impactful for Black and Brown students, who research published by the Pew Research Center shows are more likely to view themselves as gamers and to see games as positive ways to promote teamwork, communication, problem-solving, and strategic thinking (Anderson, 2015).

Research on the role games can play in education has explored this topic for decades (Stubbs & Sorenson, 2025). Tabletop role-playing games (TRPGs) can be an effective, low-cost intervention to support students’ academic, social, and emotional development. Moreover, the ways in which TRPGs can support student development are aligned with traditional learning theories posited by Bandura (1976), Vygotsky (1978), and others.

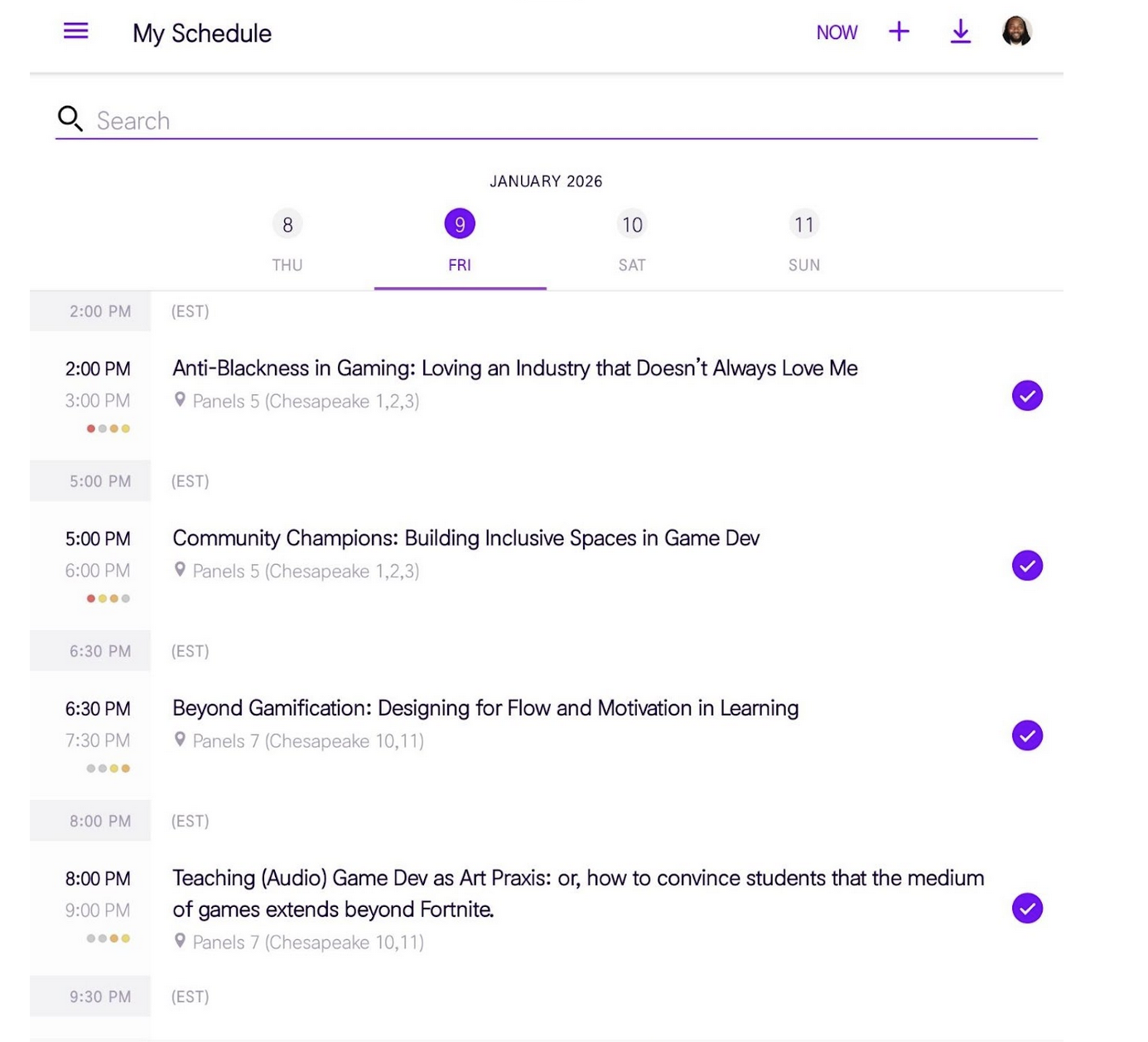

Since working in Washington, I have continued to attend conferences and engage in discussions that center on education, culture, and SEL. These days, they just look a little different.

Instead of personalized learning summits, I now attend events like the Music and Games Fest, where academics, industry professionals, and fans meet to explore topics such as how music and gaming can support mental health for young people and adults.

Instead of educational equity forums, I now attend events like BlerDCon™, where Black and Brown educators, cosplayers, and fans of anime and all things “nerdy” discuss how we can design more equitable education systems and societies.

The venues may have changed, but the work remains the same.

The work remains answering the question: how can we make school work for ALL students?

Some of the 30,000 music and gaming creators, fans, analysts, and educators who attended the 2026 Music and Games Festival (“MAGFest”) at the Gaylord National Convention Center.

MAGFest attendees are engaging in an intellectual discussion based on the author’s talk on the cultural relevance and significance of Black characters in fighting games.

Session attendees share a laugh over moments both ironic and joyous at the intersection of gaming, race, and education.

A snippet of sessions at MAGFest 2026 that centered on gaming, psychological well-being, and tenets of socioemotional learning.

References

Anderson, M. (2015, December 17). Views on gaming differ by race, ethnicity. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2015/12/17/views-on-gaming-differ-by-race-ethnicity/.

Akamatsu, D. & Gherghel, C. (2025). Failure beliefs in school and beyond: From the perspective of social and emotional learning. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy, 5, pp. 1 – 8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sel.2025.100095.

Attaya, M.K. & Hilliard, L.J. (2023). Applying critical race theory to social and emotional learning programs in schools. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy, 1, pp. 1 – 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sel.2023.100005.

Bandura, A. (1976). Social Learning Theory. Prentice-Hall.

Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning. (2020). CASEL’S SEL framework: What are the core competence areas and where are they promoted? [Policy Brief].

Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning. (n.d.). Fundamentals of SEL. https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/.

Cipriano, C., Ahmad, E., McCarthy, M.F., Ha, C., & Ross, A. (2025). Illustrating the need for centering student identity in universal school-based social and emotional learning. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy, 5, pp. 1 – 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sel.2025.100088.

Ginwright, S.A. (2010). Black youth rising: Activism and radical healing in urban America. Teachers College Press.

McGee, E.O. & Stovall, D. (2015). Reimagining critical race theory in education: Mental health, healing, and the pathway to liberatory praxis. Educational Theory, 65(5), pp. 491 – 511. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12129.

Mehta, J. (2014, June 20). Deeper Learning has a race problem. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-deeper-learning-has-a-race-problem/2014/06.

Milner, H.R. (2007). Race, culture, and researcher positionality: Working through dangers seen, unseen, and unforeseen. Educational Researcher, 36(7), pp. 388 – 400. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X07309471.

Stubbs, R. & Sorensen, N. (2025). Tabletop role-playing games and social and emotional learning in school settings. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy, 5, pp. 1 – 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sel.2025.100090.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.