Educators often treat school culture and climate as interchangeable terms; however, they are distinct concepts. As noted in this month’s Director’s Desk article, it is the culture – the set of shared values, beliefs, and traditions – that influences people’s attitudes and sets the tone for their behavior. However, researchers often focus on school climate. That is probably because “climate” is easier to operationalize, including the attitudes, behaviors, and experiences of the students, teachers, and staff.

Interestingly, for such an important concept, there appears to be no clarity on a definition. As noted by Rudasill et al. (2018), “School climate has been widely examined… However, there is little conceptual consensus… offering inconsistent guidance for researchers.” They proposed the “Systems View of School Climate (SVSC)” that defines school climate as “the affective and cognitive perceptions regarding social interactions, relationships, values, and beliefs held by students, teachers, administrators, and staff within a school.”

For someone who devoted many years working in large urban districts evaluating schools, confusion about defining school climate is, on the one hand, surprising in that the quality of a school might be simplified to two essential and fundamental questions:

- Does the school have a positive academic focus, ensuring that instruction is of sufficient quality to challenge and support students’ academic success?

- Do the students, teachers and parents or families like their school and feel physically and emotionally safe, respected, and supported there?

On the other hand, it is not surprising that researchers have had difficulty defining school climate, given that schools are highly complex systems. As several have noted, measuring climate is not a straightforward matter. “School climate is described as a complex construct, yet it is often measured as a unidimensional factor, and (there is) little agreement guiding measurement or models” (Rudasill et al., 2018).

Among the confounding factors in defining climate is the academic successes or failures of a school. While many of the social and emotional components of a school’s environment are unrelated to its students’ academic success, disregarding student achievement would overlook the institution’s central purpose. However, it is not uncommon for students and teachers (and even parents) to have positive perceptions about their school, even when there has been a long history of low student achievement. A colleague referred to such cases as “Happy Schools.”

Some researchers have designated this factor as the “academic climate” (Wang & Degol, 2016). Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for educators, even senior leaders, to believe there are barriers preventing children from learning – e.g., poverty, insufficient resources, or lack of parental support. Where these are the prevalent views, it is not surprising that the school’s academic focus is weak. Still, in other respects, the school might be viewed as a “happy” place to work and go to school.

Of course, great schools are more than academics. A middle school principal once told me that the district’s “cumbersome” formative assessment program was undermining his primary goal: to ensure that every child left school each day thinking that they had a great day.

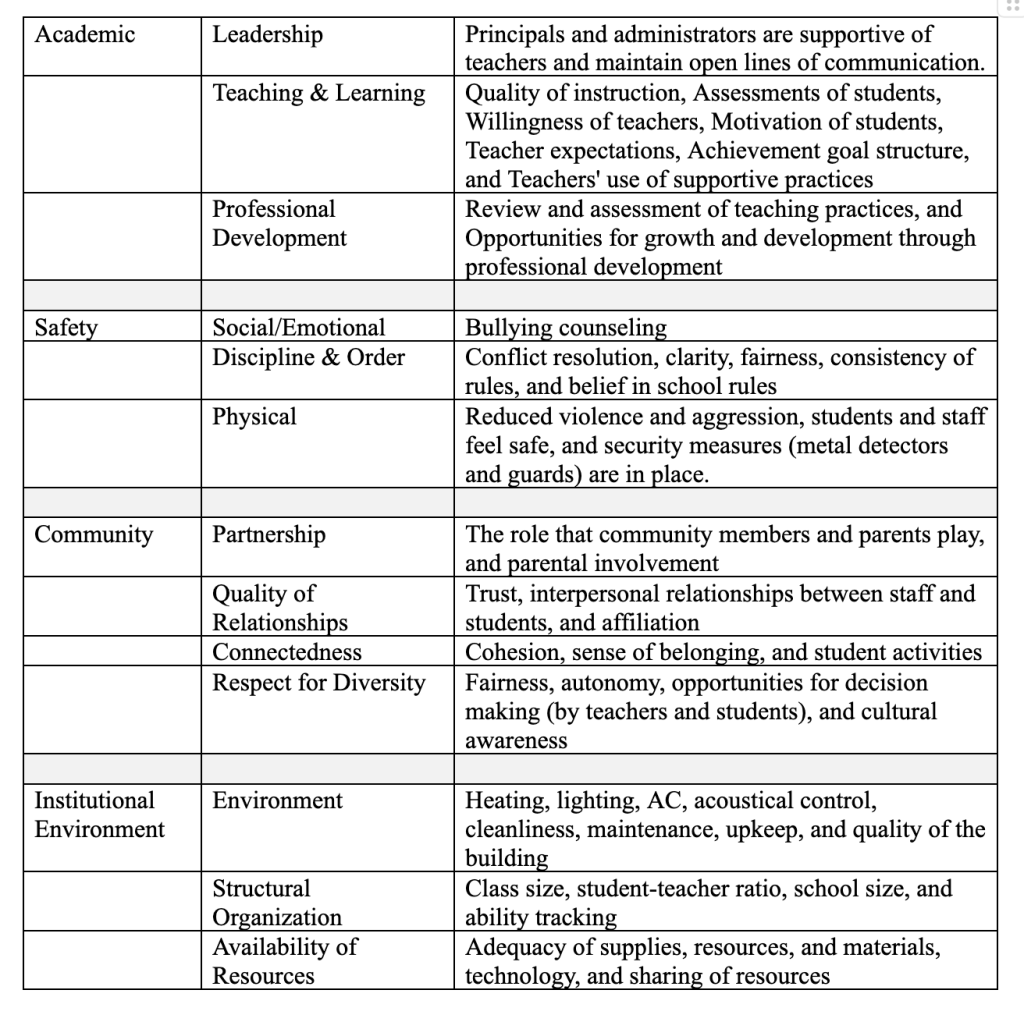

According to researchers Wang & Degol (2016), the “multidimensionality” of school climate is defined in four ways:

- Academic climate – focuses on the overall quality of the academic atmosphere, including curricula, instruction, teacher training, and professional development.

- Community – stresses the quality of interpersonal relationships within the school.

- Safety – represents the degree of physical and emotional security provided by the school, as well as the presence of effective, consistent, and fair disciplinary practices.

- Institutional environment – reflects the organizational or structural features of the school environment.

“Collectively, these four dimensions encompass just about every feature of the school environment that impacts student cognitive, behavioral, and psychological development” (see table below). However, the seminal question is which components capture the essential factors of a great school and great school culture and climate.

Table: Conceptualization and Categorization of School Climate (Wang & Degol, 2016)

Academic Climate

As recent research on the Science of Reading (SoR) has shown, programs and curriculum play a vital role in the success of the instructional program and, therefore, the climate of a school. According to Helwig (2017), a critical feature of any program is that it must be easily implemented by all personnel in the school, including inexperienced and first-year teachers.

Of course, top-down decisions open the administration to criticism and often lead to unhappy classroom teachers and school administrators. The same could be said about poor or insufficient training, frequent programmatic changes, and short implementation timelines.

To be sure, there is no substitute for well-trained, effective teachers, and given today’s high turnover rate (i.e., 10% annually), staffing is a significant challenge to school quality and culture (Diliberti & Schwartz, 2025).

Along with effective, well-trained teachers, the most critical factor impacting a school and its school climate is the school leader. However, the ideal qualities of great principals are not universally agreed upon. For example, some educators strongly believe that principals must have autonomy to make key decisions about their school, such as budget, staffing, curriculum/programs, class size, hiring, scheduling, and approaches to discipline. However, many superintendents would argue that it is their job to determine many of those decisions.

To most teachers’ relief, many principals do not want to be involved in teachers’ classroom work. However, I would argue that the school leader’s absence from daily instruction is the single most significant detriment to academic culture and the low academic performance of students. This does not mean meaningless perfunctory visits to classrooms that great teachers only find professionally demeaning and pointless.

The principal’s instructional role is particularly critical at the elementary level, where children learn to read and acquire essential math skills. A significant part of my responsibility over almost forty years (across nine public school districts) was to identify high-performing (and low-performing) schools and the factors that accounted for their success. Although they had different styles and personalities, the most successful elementary school principals were always intimately involved in daily instruction. One successful principal, in a particularly dysfunctional district, actually developed the school’s curriculum. In one school, a group of teachers told me that the principal “wore them out” helping them develop their daily lessons. Perhaps, surprisingly, the teachers seemed to like and admire their very hands-on instructional leader. In two other high-performing “National Blue Ribbon Schools,” the principals granted their teachers nearly complete autonomy over the curriculum. However, the principals regularly taught model lessons, personally led the skills math program, and closely monitored the implementation of what they believed were the key programmatic components of the academic program.

What is important to understand is that exceptional teachers and school leaders have not found some difficult, secret program. It is also not because they have supernatural charismatic personalities. What they understand is basic learning principles, the importance of perseverance and repetition, and effective school organizations and systems.

Unfortunately, the research on school improvement and effective schools has not captured these critical qualities. What we typically find in the research on effective schools and school improvement is discussions of general concepts that fail to detail the key levers of excellent schools. For example, the Wallace Foundation (2012) identified “five functions of the effective principals: 1) Shaping a vision of academic success for all students, 2) Creating a climate hospitable to education, 3) Cultivating leadership in others, 4) Improving instruction, and 5) Managing people, data, and processes to foster school improvement.

Of course, all those things are important, but what do they look like operationally in a real high-performing school? Typically, the research does not provide those details. It may be that to identify and understand the differences, you may need to be “on the ground” in a district every day, where you can observe and get to know the truly exceptional school leaders and what makes them unique.

Thus far, the focus has been on the components impacting academic outcomes. However, the quality of a school and its climate encompasses a range of factors, including psychological, interpersonal, emotional, physical, and organizational elements. These latter qualities are primarily addressed through what Wang & Delgol (2016) categorize as the Community and the physical and emotional Safety dimensions of school culture/climate.

“The community domain of school climate is defined as having four dimensions: quality of interpersonal relationships, connectedness, respect for diversity, and community partnerships.

- Quality of interpersonal relationships refers to the consistency, frequency, and nature of the relationships that occur within the school… (leading to) mutual feelings of support, trust, respect, and caring characterize positive interpersonal relationships.

- Connectedness, or a sense of belonging, is what students experience when they feel accepted, included, and valued in school.

- Respect for diversity refers to the presence of cultural awareness, appreciation, and respect for all. Teachers who cultivate culturally sensitive classrooms are those who encourage student interests and autonomy.

- Community partnership refers to the role that parents and other community members play in the school setting. A strong community partnership is characterized by parental involvement in the school, including regular communication with teachers and other personnel” (Wang & Degol, 2016).

When my middle school principal colleague told me that his primary goal was to “ensure that every child left school each day thinking that they had a great day,” he was primarily referring to the first three of these components – quality interpersonal relationships, connectedness, and respect for diversity.

The school safety domain of school climate is most commonly defined in three dimensions: physical safety, emotional safety, and order and discipline (Wang & Degol, 2016).

- The physical safety of a school refers to the degree to which violence, aggression, and victimization are present, as well as the measures taken to ensure the safety of its members.

- Emotional safety is described as the presence of caring and supportive staff, availability of counseling services for students struggling with mental health challenges, and an absence of verbal bullying or harassment.

- Order and discipline refer to the degree to which students subscribe to school rules, the consistency and fairness of discipline practices, and how incivility or disorder are handled” (Wang & Degol, 2016).

“Restorative practices (RP) is a relatively new school intervention aimed at whole school change: reducing punitive disciplinary measures, eliminating disciplinary inequities, and promoting a more positive school environment” (Grant et al., 2022).

While students’ emotional and physical safety should be a minimum expectation, too often, that low bar has not been met. Sadly, I have worked in and visited high schools where teachers only reluctantly ventured into the halls during class changes.

The final component discussed by Wang & Degol (2016) relates to the “institutional environment.” They state, “The tangible, sensory quality of an environment plays a great part in shaping the experiences people have in that environment.” While that may be true, generally, the size, space, age, and heating and cooling systems of a building, contrary to the author’s view, play a relatively minor role in the teachers’ “effectiveness and instructional practices.” There are many new facilities with poor social, emotional, and academic climates, as well as many old buildings with excellent climates.

However, some features of the “structural organization” are significant. While the research on school size and class size are not unequivocal, common sense suggests that they play an important role in teacher attitudes and effectiveness, student outcomes, and school climate (Simon & Johnson, 2015). Regarding class size, I am not aware of any teachers who would prefer 30 students in a class over 20, or 20 students in a class over 15.

At the high school level, software is now available to help track chronic absenteeism, truancy, course failure rates, mobility, and progress toward graduation, which can undoubtedly be helpful. However, compared to other factors, these play a relatively minor role in school climate.

Finally, the availability of resources is an important issue, and is frequently raised in relation to both equity and student outcomes. In cases where funding is a significant issue, states and districts must ensure that teachers and students have access to the necessary technology, tools, and resources. As Wang & Degol (2016) argue, “Although the core of instruction comes from the interaction between teachers and students, that interaction is frequently facilitated by the equipment, materials, and supplies of teaching.”

An important question regarding school climate and culture is whose opinions matter the most.

Indeed, teachers’ perspectives are important (although rarely acted upon), and school leaders can provide vital information from their experience and perspective. However, the bottom line is that if we want to know how our schools are doing, we need to ask the students. Do they feel confident and successful? Do they feel engaged and challenged? Do the students feel safe, or are they frequently bullied? Do they come to school regularly? Do they think the teachers and administrators support and respect them? Do they have positive relationships with other students? Do they leave school each day feeling like they had a great day and want to come back the next day?

Numerous factors influence a school’s social, emotional, and academic climate. At the top of the list are the teachers and the school leader. There is little disagreement about the critical importance of having highly effective teachers in every classroom. Interestingly, however, while educators often refer to principals as instructional leaders, in most schools, they play a limited role in the daily work of classroom teachers. That must change if more of our urban schools are to become high-performing institutions with great school culture.

Of course, achievement is just one of the purposes of an education. It is equally vital that our schools ensure that their students feel respected, valued, and cared for. In addition, our schools must help students develop socially and emotionally so that they respect others, feel confident and capable, and learn to persevere and succeed. These are not simple or easy goals. However, the sad reality is that in too many cases, students do not even feel physically or emotionally safe in their school. Many schools have turned to social justice programs and restorative practices to combat some of these challenges. These will be critical research areas going forward, and at the center of our work at the National Center for the Elimination of Educational Disparities (NCEED) and future editions of the NCEED Equity Exchange newsletter.

———————————-

This article examines school cultures and the attitudes, practices, and leadership that produce positive cultures – touching on virtually all of NCEED’s pillars (learn more here).

In her Director’s Desk article, NCEED Director, Dr. Meria Carstarphen, addresses some of the key issues urban school leaders must address today. August’s “By-the-Numbers” article focuses on Chronic Absenteeism and some of the qualities of school culture that encourage students to come to school regularly.]

—————————————————————-

References:

Barkley, B., Lee, D., & Eadens, D. (2014). Perceptions of School Climate and Culture. EJEP: EJournal of Education Policy.

Bradshaw, C. P., Cohen, J., Espelage, D. L., & Nation, M. (2021). Addressing school safety through comprehensive school climate approaches. School psychology review, 50(2-3), 221-236.

Darling-Hammond, L., Ross, P., & Milliken, M. (2006). High school size, organization, and content: What matters for student success?. Brookings papers on education policy, (9), 163-203.

Diliberti, M. K., & Schwartz, H. L. (2025). Educator Turnover Continues Decline Toward Pre-Pandemic Levels: Findings from the American School District Panel.

Durlak, J.A., Weissberg, R.P., Dymnicki, A.B., Taylor, R.D. & Schellinger, K.B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14678624

Fletcher, A. (2015). School culture and classroom climate. In Prevention science in school settings: Complex relationships and processes (pp. 273-285). New York, NY: Springer New York.

Foley, E. M., Klinge, A., & Reisner, E. R. (2007). Evaluation of New Century High Schools: Profile of an Initiative to Create and Sustain Small, Successful High Schools. Final Report. Policy Studies Associates, Inc.

Grant, A.A., Mac Iver, D.J., & Mac Iver, M.A. (2022). The Impact of Restorative Practices with Diplomas Now on School Climate and Teachers’ Turnover Intentions: Evidence from a Cluster Multi-Site Randomized Control Trial. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness.

Helwig, B. (2017). Stop-Gap Literacy and Numeracy Resources. https://www.thenew3rseducationconsulting.com/resources.

Hutton, D. M. (2018). Critical factors explaining the leadership performance of high-performing principals. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 21(2), 245–265.

Iatarola, P., Schwartz, A. E., Stiefel, L., & Chellman, C. C. (2008). Small schools, large districts: Small-school reform and New York City’s students. Teachers College Record, 110(9), 1837-1878.

Kutsyuruba, B., Klinger, D. A., & Hussain, A. (2015). Relationships among school climate, school safety, and student achievement and well‐being: a review of the literature. Review of Education, 3(2), 103–135.

Lee, M., & Louis, K. S. (2019). Mapping a strong school culture and linking it to sustainable school improvement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 84-96.

Rudasill, K. M., Snyder, K. E., Levinson, H., & L. Adelson, J. (2018). Systems view of school climate: A theoretical framework for research. Educational psychology review, 30(1), 35-60.

Simon, N., & Johnson, S. M. (2015). Teacher turnover in high-poverty schools: What we know and can do. Teachers College Record, 117(3), 1-36.

Stiefel, L., Wiswall, M., Schwartz, A.E., & Debraggio, E. (2012). Does Small High School Reform Lift Urban Districts? Evidence from NYC. Econometrics: Single Equation Models eJournal.

Wang, M. T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational psychology review, 28(2), 315-352.

Wallace Foundation. (2012). The school principal as leader: Guiding schools to better teaching and learning. New York, NY: Author. Retrieved from http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/school-leadership/effective-principalleadership/Documents/The-School-Principal-as-Leader-Guiding-Schools-to-Better-Teaching-and-Learning.pdf