As most Maryland educators are aware, the state has approved new legislation regarding literacy instruction in our public schools. The new requirements include the following:

- All Pre-K students in Maryland must receive instruction and curriculum aligned with the Science of Reading, as defined by the Maryland Early Learning Standard.

- All PreK-3 students must receive Tier I literacy instruction, also known as core instruction, aligned to the science of reading; and

- Each student’s reading competency must be assessed throughout the year.

Further, “Each PreK-3 student who exhibits difficulties in reading shall receive supplemental instruction through a reading program aligned to the science of reading… The system of assessments districts use must include statewide universal screening, diagnostic surveys, and progress monitoring of student growth toward grade-level reading. Beginning in SY 2025-2026, MSDE will release a list of vetted and approved universal screeners to be administered three times per year: at the beginning of the year, the middle of the year, and the end of the year. The screener will be used to identify students with early warning signs of reading difficulties… (and) at a minimum, measure phonological and phonemic awareness, sound-symbol recognition, decoding, fluency, and rapid automatic naming. Measures may also include additional subtests such as encoding and reading comprehension… Additional diagnostic tools should be identified and administered to support teachers in targeting instruction based on student needs” (Maryland State Department of Education, 2024).

Fortunately, many Maryland teachers and administrators already have experience with reading screeners and diagnostic assessments. In 2024, the Maryland State Department of Education, AIM Institute for Learning and Research, and Maryland Initiative for Literacy and Equity (MILE) partnered to evaluate “literacy instruction across all 24 Maryland LEAs.” (Here referred to as the MILE reports.) Based on the MILE reports, at least 18 of the 24 Maryland school districts already use some type of reading screener. The most commonly used assessment reported was DIBELS. Other widely used screening tools included NWEA MAP and i-Ready assessments. One district also reported using the Spanish version of mCLASS, Lectura, in their two-way immersion programs. Several states publish lists of approved screeners and outline the components of each approved assessment. For example, DIBELS is reported to assess the following K-2 skills:

- Phonemic awareness (phoneme isolation, phoneme segmentation)

- Word Reading/Word Identification

- Letter identification

- Decoding Nonsense Words

- Passage Reading Fluency

- Reading Comprehension

- Rapid automatized naming: Letter Naming Fluency task

- Letter-sound correspondence (A separate score as part of Decoding Nonsense Words)

Other skills included on some other screeners include:

- Phonological awareness (rhyme, syllable, onset rime)

- Vocabulary

- Listening Comprehension/Oral Language Comprehension

(See the Massachusetts Department of Education Approved Early Literacy Universal Screening Assessments. https://www.doe.mass.edu/instruction/at-a-glance.docx.)

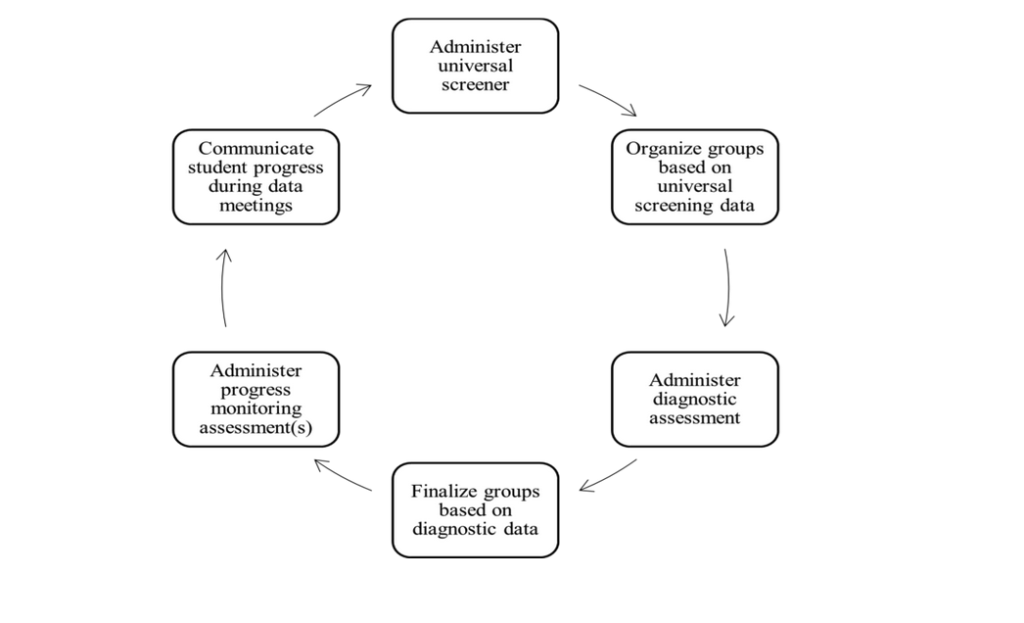

The use of a universal screener, according to Irey et al. (2025), is not sufficient, however. They argue that once the initial screening is completed, a deeper assessment is required to identify a student’s specific needs. “Screening tools do indicate where students stand relative to grade-level expectations for specific skills, but they do not provide a detailed breakdown of students’ competencies with specific skills that teachers can address” (Brooke, 2025). The following graphic shows the complete assessment cycle Brooke describes.

Beginning in SY 2027-208, the retention component of the state’s new policy will go into effect. However, the policy states that retention decisions must use “Triangulated data from valid and reliable multiple measures, such as curriculum-based measures, diagnostic assessments, and benchmark assessments, or other assessments… Screener data and/or benchmarks should not be used in isolation for promotion purposes.”

From a psychometric perspective, of course, critical questions relate to the reliability and validity of the assessments. Some studies have looked at this question in relation to predictions of state summative test results (Thomas, 2021). Others have examined the strength of associations among various screeners (Catts et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2015).

Of course, from the practitioner’s perspective, there are two crucial questions. First, do the screeners accurately distinguish between the students in need of tiered support and those who do not (Kilgus et al., 2014; VanMeveren et al., 2020).

“Diagnostic accuracy is a component of consequential validity designed to… maximize the number of students correctly identified as high risk and low risk” (Kilgus et al., 2014). It “uses conditional probability statistics including (a) sensitivity, (b) specificity, (c) positive predictive power, and (d) negative predictive power” (VanMeveren et al., 2020).

“Sensitivity refers to the degree to which a criterion assessment identifies students who are at risk… A screener with 63% sensitivity accurately identifies 63% of individuals who have a reading problem. Specificity describes the ability of the assessment to correctly identify students without a condition… Sensitivity and specificity are complementary and used to evaluate and compare different assessments on the same criterion. Ideally, a test would have 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity.

“Although sensitivity and specificity provide valuable information regarding assessments, they do not take into consideration false positives and false negatives. For this reason, positive and negative predictive powers are also used. Positive and negative predictive power describe how likely a student is to have a condition given the results of a screener. Positive predictive power describes the conditional probability that a student identified as at risk on a screener is also identified by the criterion measure as at risk. Conversely, negative predictive power reflects the probability that a student identified as proficient on the screener is also identified as proficient on the criterion measure” (VanMeveren et al., 2020).

For the practitioner, the second important question is what instructional strategies and programs to employ at each tier – I, II, and III. DIBELS, i-Ready, MAP, and other valid and reliable assessments have been in use in Maryland and across the U.S. for several years. In addition, well-known and well-respected phonics-based interventions have also been widely used for several years. Yet, on the most recent NAEP reading assessment (2024), only 30% of the Maryland 4th graders scored at or above “proficient,” and 60% of the state’s “economically disadvantaged” 4th grade students scored below the “basic” level (NAEP, 2024). The question we must ask, and that will be central to our work at the National Center for Elimination of Educational Disparities (NCEED), is how our programs and instructional practices must be adjusted or expanded to produce the results our teachers know they can achieve and the outcomes our children and families need and deserve. The Maryland Comprehensive PreK-3 Literacy Policy lays out the tasks that must be implemented. As renowned literacy expert Louisa Moats challenges, “Just about all children can be taught to read and deserve no less from their teachers. Teachers, in turn, deserve no less than the knowledge, skills, and supported practice that will enable their teaching to succeed.” The gaps between more advantaged and less advantaged students “are the result of differences in students’ opportunities to learn—not their learning abilities” (Moats, 2024).

[The October Equity Express will include an article on The Reading Achievement Gap, for a more detailed look at the Maryland and national achievement data.]

References:

Catts, H. W., Petscher, Y., Schatschneider, C., Sittner Bridges, M., & Mendoza, K. (2009). Floor effects associated with universal screening and their impact on the early identification of reading disabilities. Journal of learning disabilities, 42(2), 163-176.

Irey, R., Silverman, R., Pei, F., & Gorno-Tempini, M. L. (2025). The importance of early literacy screening. Phi Delta Kappan, 106(7-8), 28-33.

Kilgus, S. P., Methe, S. A., Maggin, D. M., & Tomasula, J. L. (2014). Curriculum-based measurement of oral reading (R-CBM): A diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis of evidence supporting use in universal screening. Journal of School Psychology, 52(4), 377-405.

Moats, L. C. (2020). Teaching Reading” Is” Rocket Science: What Expert Teachers of Reading Should Know and Be Able to Do. American Educator, 44(2), 4.

NAEP, 2024. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2024/pdf/2024220MD4.pdf

Odegard, T. N., Farris, E. A., Middleton, A. E., Oslund, E., & Rimrodt-Frierson, S. (2020). Characteristics of students identified with dyslexia within the context of state legislation. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(5), 366-379. https://www.improvingliteracy.org/resource/screening-for-reading-risk-what-is-it-and-why-is-it-important

Parker, D. C., Zaslofsky, A. F., Burns, M. K., Kanive, R., Hodgson, J., Scholin, S. E., & Klingbeil, D. A. (2015). A brief report of the diagnostic accuracy of oral reading fluency and reading inventory levels for reading failure risk among second-and third-grade students. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 31(1), 56-67.

Petscher, Y., Pentimonti, J., & Stanley, C. (2019). Reliability. Improving Literacy Brief: Understanding Screening. National Center on Improving Literacy.

Thomas, A. S., & January, S. A. A. (2021). Evaluating the criterion validity and classification accuracy of universal screening measures in reading. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 46(2), 110-120.

Wilkins, B. (2025). Using diagnostic assessments to improve data use. Phi Delta Kappan, 106(7-8), 34-38. https://kappanonline.org/using-diagnostic-assessments-to-improve-data-use/

VanMeveren, K., Hulac, D., & Wollersheim-Shervey, S. (2020). Universal screening methods and models: Diagnostic accuracy of reading assessments. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 45(4), 255-265.