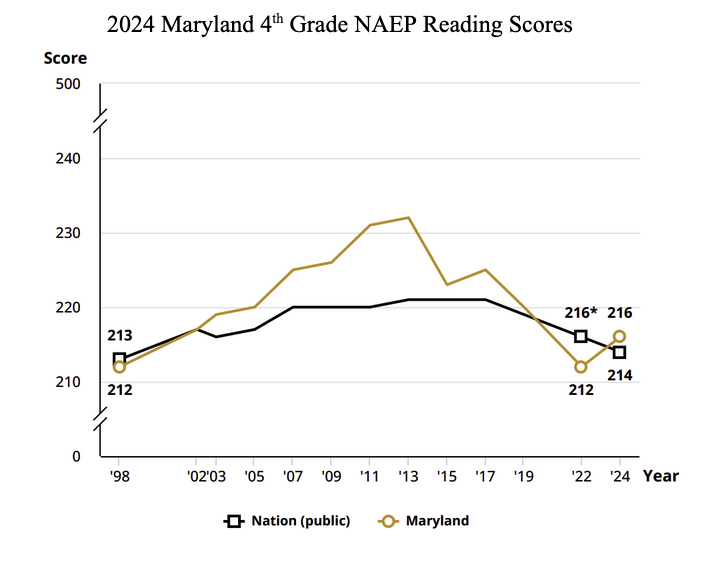

“Since 2013, Maryland students have experienced a decline in reading performance, falling from third to forty-first in the nation on the Grade 4 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Reading Assessment. This alarming decrease underscores the urgent need to address reading proficiency, particularly for students with reading deficiencies, those living in poverty, multilingual learners, and students of color” (Maryland Comprehensive PreK-3 Literacy Policy, 2024).

Some researchers have questioned the appropriateness of the NAEP standards (Harvey, 2018; Forzani et al., 2022). However, even if the proficient standard tends to overestimate the number of poor readers in the U.S., an examination of performance at the basic and below-basic levels demonstrates the desperate need for significant changes in our instructional practices, particularly for economically disadvantaged, at-risk, and historically underserved children.

On the 2024 NAEP reading assessment, 60% of Maryland’s “economically disadvantaged” 4th-grade students scored below the Basic level, and only 16% scored at or above the proficient level. Maryland 8th graders obtained similar results. 49% of Maryland’s “economically disadvantaged” 8th-grade students scored below the Basic level, while only 17% scored at or above the proficient level (NAEP, 2024).

The 2018 NAEP Oral Reading Fluency study found that students “who perform below the NAEP Basic level on the fourth-grade NAEP Reading assessment have poor oral reading fluency and foundational skills – i.e., word reading, the ability to read familiar words with accuracy and speed, and phonological decoding, and the ability to pronounce unfamiliar words based on spelling-sound correspondences” (White et al., 2021).

According to literacy expert Louisa Moats (2020), the Simple View of Reading serves as the foundation for designing reading instruction. “It states that reading comprehension is the product of word recognition and language comprehension. Without strong skills in either domain, an individual’s reading comprehension will be compromised.”

In the 1990s, researchers Betty Hart and Todd Risley studied families from different socioeconomic levels. They found that young children were exposed to vastly different numbers of words depending on their families’ income. They reported a 32-million-word gap between children from higher-income and lower-income families, and that the differences accounted for significant differences in the children’s language skills when they entered kindergarten (Hart & Risley, 1995). In recent years, some researchers have disputed their findings, arguing that the “word gap” between poor and affluent children may not be as large as Hart and Rigley found (Williams, 2020). However, several studies have validated Hart and Risley’s findings, even as they often questioned their methods and sampling (Gilkerson et al., 2017; Romeo et al., 2018; Sindt, 2020; Sperry et al., 2019).

Hart and Risley used audiotape recordings of family discussions as the children aged from 12 to 36 months. Several more recent studies utilized the Language Environment Analysis (LENA) System, which provides accurate and reliable all-day recordings that are “automatically analyzed by using speech recognition technology, generating estimates of adult word exposure (including both child-directed and overheard speech), as well as adult-child conversational turn-taking and child vocalization frequency.” One study, for example, included over three thousand 12-hour recordings (Gilkerson et al., 2017).

Several ethnographic studies have examined the relationship between parents’ socio-economic status (SES) – education, income, and occupational status – and families’ educational and language “habits,” school readiness, and children’s later performance in school (i.e., oral language, vocabulary, and decoding). In early studies, “cognitive support” was measured by “the number of children’s books in the home, parental help with learning letters, numbers, and shapes, and the frequency of attending performances or visiting museums. That is, the organized educational activities that parents undertake with their child” (Durham et al., 2007).

In a 2007 study of 502 white students from the central Midwest, researchers found positive effects between families’ SES background and the children’s oral language skills entering kindergarten and later elementary school performance. “Not surprisingly, kindergarten language skills have their strongest effect on second-grade reading… overwhelmingly, the positive effects of SES background on elementary school performance are explained by (a) the relationship between the mother’s education and children’s oral language skill when they enter kindergarten and (b) the relationship between the child’s oral language skill and later elementary school performance. This indicates that the typically more positive school performance by children from higher-SES families is largely determined by differential oral language skills that are provided to their children by more highly educated parents” (Durham et al., 2007).

Farkas and Beron (2004) found that “significant differences in vocabulary knowledge across SES groupings developed by 36 months of age, increased further through age 5… These SES-related differences in children’s vocabulary knowledge are strongly affected by the mother’s vocabulary knowledge and the level of cognitive stimulation in the home.” Lonigan et al. (2000) found that preschool oral language development is the key precursor to first-grade reading success, and that phonological sensitivity and letter knowledge accounted for 54% of the variance in kindergarteners’ and first graders’ word decoding abilities. Lareau (2003) coined the term “concerted cultivation.” She argued that children of middle-class parents “engage their children in conversations that are more interactive, and more often involve reasoning.”

Gibbs (2025), Moats (2020), Marzano (2014), and others explain these findings in relation to children’s “opportunity” to learn. “Imagine that a child’s language bank is full of vocabulary, knowledge of how words make sentences, and information about the world. When the child begins to read, they will be better able to connect the words on the page to all these things… From birth to about age six, children are considered prereaders. They are learning sounds, letters, words, phrases, and what all those things mean. They begin to learn about books… They go places with adults and experience new things. Even commonplace things, such as shopping or taking the bus, provide new experiences for children, especially if the adults talk with the children about what is going on. For example, talking about what you have to do to take the bus, the colors of the packages at the store, or how you pay for something provides new information for children to deposit in their language bank.” As they get older, “They then bring what they know about the world, including topics like science or history, and use that information to make connections and understand what they read” (Gibbs, 2025).

“Learning to read is not natural or easy for most children… unlike spoken language, which is learned with almost any kind of contextual exposure… (However) This we know: reading failure can be prevented in all but a small percentage of children with serious learning disorders. It is possible to teach most students how to read if we start early and follow the significant body of research showing which practices are most effective. Students living in poverty, students of color, and those eligible for remedial services can become competent readers – at any age. Persistent “gaps” between more advantaged and less advantaged students can be narrowed and even closed. Fundamentally, these gaps are the result of differences in students’ opportunities to learn—not their learning abilities” (Moats, 2020).

“The tragedy is that most reading failure is unnecessary. For children growing up in under-resourced communities and attending under-resourced schools, the incidence of reading failure is astronomical and completely unacceptable. We now know that classroom teaching itself, when it includes a range of research-based components and practices, can prevent and mitigate reading difficulty. Although home factors do influence how well and how soon students read, informed classroom instruction that targets specific language, cognitive, and reading skills beginning in kindergarten enhances success for all but a very small percentage of students with learning disabilities or severe dyslexia. Researchers now estimate that 95 percent of all children can be taught to read by the end of first grade…

“While parents, tutors, and the community can contribute to reading success, classroom instruction is the critical factor in preventing reading problems… However, to be clear, although the day-to-day work is teachers’ responsibility, students’ reading success is our shared responsibility” (Moats, 2020).

Durham et al. (2007) argue “that middle-class parents make a ‘project’ of the child’s preparation for, and performance at, school, and this contributes to the better school performance of children from higher social class backgrounds.” A principal of a National Blue Ribbon Elementary School once told me that it was when he finally understood this difference that he changed his school’s approach. He realized many of his students lacked the fundamental skills necessary for success – basic reading and math skills. In reading, the critical objective was to ensure that the school leveled the “word recognition and language comprehension” playing field for all the children as quickly as possible so they could fully access the curriculum.

Equity – leveling the playing field – is at the heart of NCEED’s mission (learn more about us here). Our faculty and staff collaborate with families and communities to reduce the gaps between the advantaged and disadvantaged. We support and research schools’ best instructional practices. Now, we are developing strategies and studies to support the implementation of the Maryland Comprehensive PreK-3 Literacy Policy because we know that to succeed, every member of the community must make reading their “project.”

[This month’s Equity Express newsletter includes two additional articles. In celebration of National Principals Month, the Director’s Desk article focuses on Principal Leadership and Effective Change. In the third article, Elevating Equity: Supporting Black Male Educators on the Path to National Board Certification, Esther Ward, National Board Certification Coordinator, and Dr. Simone Gibson, Assistant Director for Literacy at NCEED and Associate Professor in the Department of Teacher Education at Morgan State University, discuss strategies to increase recruitment of Black male teachers.]

——————————————

References:

Bandeira de Mello, V., Bohrnstedt, G., Blankenship, C., & Sherman, D. (2015). Mapping State Proficiency Standards onto NAEP Scales: Results from the 2013 NAEP Reading and Mathematics Assessments. NCES 2015-046. National Center for Education Statistics.

Betty Hart and Todd Risley, 1995, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children, P.H. Brookes Publisher.

Catts, H. W., Petscher, Y., Schatschneider, C., Sittner Bridges, M., & Mendoza, K. (2009). Floor effects associated with universal screening and their impact on the early identification of reading disabilities. Journal of learning disabilities, 42(2), 163-176.

Conor P. Williams, October 13, 2020, New Research Ignites Debate on the “30 Million Word Gap,” https://www.edutopia.org/article/new-research-ignites-debate-30-million-word-gap

Durham, R. E., Farkas, G., Hammer, C. S., Tomblin, J. B., & Catts, H. W. (2007). Kindergarten oral language skill: A key variable in the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 25(4), 294-305.

Farkas, G., & Beron, K. (2004). The detailed age trajectory of oral vocabulary knowledge: Differences by class and race. Social Science Research, 33(3), 464-497.

Forzani, E., Afflerbach, P., Aguirre, S., Brynelson, N., Cervetti, G., Cho, B. Y., … & Uccelli, P. (2022). Advances and missed opportunities in the development of the 2026 NAEP Reading Framework. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 71(1), 153-189.

Gibbs, T. (2025). NWEA. All about language comprehension: What it is and how it can help your child read. https://www.nwea.org/blog/2025/all-about-language-comprehension-what-it-is-and-how-it-can-help-your-child-read/#.

Gilkerson, J., Richards, J., Warren, S., Montgomery, J. K., Greenwood, C. R., Kimbrough Oller, D., & Paul, T. (2017). Mapping the early language environment using all-day recordings and automated analysis. American journal of speech-language pathology, 26(2), 248-265.

Harvey, J. (2018). The problem with “proficient.”. Educational Leadership, 75(5), 64-69.

Hernandez, D. J. (2011). Double jeopardy: How third-grade reading skills and poverty influence high school graduation. Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Irey, R., Silverman, R., Pei, F., & Gorno-Tempini, M. L. (2025). The importance of early literacy screening. Phi Delta Kappan, 106(7-8), 28-33.

Isaacs, J. B. (2012). Starting school at a disadvantage. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved August 2025.

Isaacs, J. B. (2012). Starting School at a Disadvantage: The School Readiness of Poor Children. The Social Genome Project. Center on Children and Families at Brookings.

Ji, C. S., Yee, D. S. W., & Rahman, T. (2021). Mapping State Proficiency Standards onto the NAEP Scales: Results from the 2019 NAEP Reading and Mathematics Assessments. NCES 2021-036. National Center for Education Statistics.

Johnston, P. (2019). Talking children into literacy: Once more, with feeling. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 68(1), 64-85.

Kilgus, S. P., Methe, S. A., Maggin, D. M., & Tomasula, J. L. (2014). Curriculum-based measurement of oral reading (R-CBM): A diagnostic test accuracy meta-analysis of evidence supporting use in universal screening. Journal of School Psychology, 52(4), 377-405.

Farkas, G., & Beron, K. (2004). The detailed age trajectory of oral vocabulary knowledge: Differences by class and race. Social Science Research, 33(3), 464-497.

Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal childhoods. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lonigan, C. J., Burgess, S. R., & Anthony, J. L. (2000). Development of emergent literacy and early reading skills in preschool children: Evidence from a latent variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 36, 596–613.

Marzano, R. J., & Toth, M. D. (2014). Teaching for rigor: A call for a critical instructional shift. Learning Sciences Marzano Center, 1, 1-24.

Moats, L. C. (2020). Teaching Reading” Is” Rocket Science: What Expert Teachers of Reading Should Know and Be Able to Do. American Educator, 44(2), 4.

MSDE, 2024. Maryland Comprehensive PreK-3 Literacy Policy (Pg. 17). Maryland State Department of Education. https://marylandpublicschools.org/programs/Documents/ELA/PreK-Literacy-Policy-Fall-Final-a.pdf

NAEP, 2024. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2024/pdf/2024220MD4.pdf

NAEP, 2024. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2024/pdf/2024220MD8.pdf

Odegard, T. N., Farris, E. A., Middleton, A. E., Oslund, E., & Rimrodt-Frierson, S. (2020). Characteristics of students identified with dyslexia within the context of state legislation. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(5), 366-379. https://www.improvingliteracy.org/resource/screening-for-reading-risk-what-is-it-and-why-is-it-important

Romeo, R. R., Leonard, J. A., Robinson, S. T., West, M. R., Mackey, A. P., Rowe, M. L., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2018). Beyond the 30-million-word gap: Children’s conversational exposure is associated with language-related brain function. Psychological Science, 29(5), 700-710.

Sindt, A. C. (2020). The Achievement Gap Dilemma/Talking With Children Matters.

Sperry, D. E., Sperry, L. L., & Miller, P. J. (2019). Reexamining the verbal environments of children from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Child development, 90(4), 1303-1318.

Weisleder, A., & Fernald, A. (2013). Talking to children matters: Early language experience strengthens processing and builds vocabulary. Psychological Science, 24(11), 2143-2152.

White, T. G., Sabatini, J. P., & White, S. (2021). What Does “Below Basic” Mean on NAEP Reading?. Educational Researcher, 50(8), 570-573.

Williams, C. (2020). New Research Ignites Debate on the “30 Million Word Gap,”

https://www.edutopia.org/article/new-research-ignites-debate-30-million-word-gap