“Usus est magister optimus.” The literal translation is “Use is the best master,” or in modern parlance, “Practice makes perfect.” As noted in the July Equity Exchange newsletter article examining Summer Learning Loss, “most teachers and coaches emphasize approximations of perfection. No gymnast, ballerina, skater, foul-shooter, pianist, speaker, speller, writer, or reader performs tasks perfectly on the first try or the first dozen tries.”

The quote, “Success is 10% inspiration and 90% perspiration,” is often attributed to Thomas Edison (and sometimes Albert Einstein). However, it is impossible to practice or to perspire (or be inspired) if you do not come to school. The U.S. Department of Education (USDE) defines chronic absenteeism as a student missing 10% or more of school. In 2023, the U.S. rate of chronic absenteeism was 28% (U.S. Department of Education, 2023).

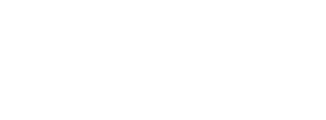

Missing 10% of school is equivalent to being absent once every two weeks. Over the typical school year, that equates to about 18 days. The 2023 chronic absenteeism rate for the State of Maryland was 32% where almost one-third of the students missed at least one day of school every two weeks. The rates by race and ethnicity are shown below (USDE, 2023).

The COVID-19 pandemic raised serious concerns about the amount of time students were missing from school. “On the most recent Nation’s Report Card survey (2022), 22% of 4th graders reported they were absent five or more days in the previous month. That is double the 2019 percentage. The results were similar for 8th graders and similar across states and subgroups of students” (NAGB, 2022). Missing 5 days per month is approximately equivalent to missing 1 day per week and 50 days per school year. At that rate, a student would miss nearly an entire school year every three years (i.e., 150 days).

As the USDE report notes, “Missing school means missing valuable instructional time and poses serious implications for students’ overall academic success and wellbeing. Research suggests that children who are chronically absent for multiple years between preschool and second grade are much less likely to read at grade level by the third grade.” In addition, “students who regularly attend school gain skills such as persistence, problem-solving, and the ability to work with others to accomplish a goal” (Malika et al., 2021).

Several studies have investigated the reasons why students are chronically absent from school, and, as is frequently noted, there are multiple, often “interconnected” factors. The USDE report identifies several of these factors, including “student disengagement, lack of access to student and family supports, and student and family health challenges as significant drivers” (USDE, 2023).

A study of over 24,000 children and youth (grades 5-12) in a “predominantly low-income minority school district” provides a more detailed and nuanced understanding of both the “risks and protective factors” affecting chronically absent (CAbs) children and adolescents (Malika et al., 2021). The study examined physical and mental health factors as well as bullying, safety, and family risk factors (such as drug use and gang membership). As the authors noted, “while CAbs is a ubiquitous problem, it should not be assumed that chronically absent youth are a homogenous group.”

In assessing physical health, the study revealed that asthma (28%) and being overweight (22%) or obese (22%) were positively associated with chronic absenteeism. In addition, a greater percentage of chronically absent students reported having “family risk factors” (47%) and felt unsafe in school (26%) or in their neighborhood (19%).

The National Center for Education Statistics (2024) revealed that “The percentage of students ages 12-18 who reported being bullied during school was lower in 2021-22 than in 2010-11 (19% versus 28%). However, there is little doubt that bullying and safety concerns result in increased student absences, particularly at the middle school level. “Bullying at school at least once a week was reported by 28 percent of middle schools, compared to 15 percent of high/secondary schools and 10 percent of elementary schools. Similarly, cyberbullying at school or away from school at least once a week was reported by 37 percent of middle schools and 25 percent of high schools, compared to 6 percent of elementary schools” (NCES, 2024).

Mental health and other social-emotional challenges can also lead to chronic absenteeism. Recent studies estimate that as many as 1 in 5 children experience a mental disorder each year, and approximately 79% of children aged 6-17 have an unmet need for mental health services (OECD, 2015). Further, Kotter has found that emotional connections are a critical component of learning (Kotter, 2012). However, research indicates that many high school students, in particular, often feel bored and disengaged (Belli, 2020; Moeller, 2020).

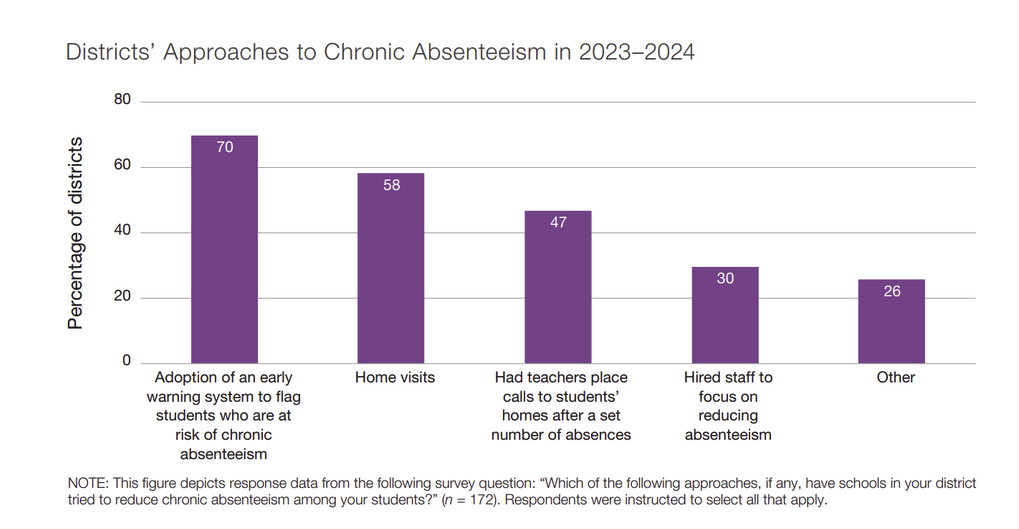

Of course, many school districts are working hard to reduce absenteeism. The figure below shows some of the strategies being employed (Diliberti et al., 2024).

According to the RAND-sponsored study, “In the 2023–2024 school year, nearly all districts (93 percent) tried at least one approach to combat chronic absenteeism” (Diliberti et al., 2024). As can be seen, the most common approach was the Adoption of an early warning system to flag students who are at risk of being chronically absent. However, one-fourth of the districts reported that “none of the approaches they had tried to reduce chronic absenteeism had been particularly effective… In interviews, 11 of 12 district leaders… speculated that a cultural shift has occurred, whereby more students and families see school as optional and of less importance. These district leaders hypothesized that chronic absenteeism would not improve without new approaches to make schools more engaging.”

In a Fordham Institute article, the authors reported that in “one study that surveyed nearly 600 public high school students in the South, 25 percent of the students felt unsafe and nearly 15 percent had avoided school in the last month because of it. Yet, the same study found that positive perceptions of the school environment – not only physical safety, but also clear rules, a sense of belonging, and positive parent-teacher relations – were associated with lower rates of absenteeism” (Northern, A. & Eggers, C., 2022). Similarly, research by Van Eck et al. (2017) “identified connections between students’ perceptions of school climate and absence rates.”

Further, in the study by Malika et al. (2021), “protective factors” for students include receiving support at school from a teacher or a staff member… and having a “personal positive growth mindset.” When teachers, staff, and school leaders provide support to their students who are most at risk, it increases attendance and factors associated with attendance, such as engagement and academic achievement. The students also exhibit more positive attitudes towards school and have better relationships with both adults and peers.

Panorama Education’s Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) survey is a tool used to understand students’ social-emotional competencies (Panorama Education, 2025). The Growth Mindset scale assesses students’ perceptions of whether they have the potential to change factors central to their school performance. “If students do not believe they can change and persevere, that they have influence over their behavior, intelligence, and talent, it is not surprising that they see no reason to go to school” (Malika et al., 2021).

So while schools must be safe, it is unlikely that improved physical safety alone will be sufficient to address the pervasive issues of chronic absenteeism in many of our schools. Today, more than ever, our schools must be both physically and emotionally safe places for students, places that support students and foster a sense of belonging. Furthermore, a growing body of research indicates that social-emotional development enables students to enhance their academic tenacity and resilience, as well as develop cognitive skills that facilitate full engagement in the curriculum (Durlak et al., 2011). “SEL supports are particularly important for children who have experienced trauma or stress, such as in low-income communities where poverty is a significant risk factor and linked with other risk factors such as housing instability, food instability, poor nutrition, and lack of adequate health care” (Alegria et al., 2010).

More generally, school climate is a widely recognized predictor of students’ social functioning and emotional health. A healthy or positive school climate fosters an environment conducive to improved academic functioning. Literature suggests that key aspects of school climate, including student connectedness with school, engagement in school activities, and perceptions of school safety, may be important determinants of attendance (Van Eck et al., 2017).

This month’s Equity Exchange article, “Climate, Culture, Equity, and Achievement,” examines school cultures and the attitudes, practices, and leadership that produce positive physical and emotional safe environments – touching on virtually all of NCEED’s pillars.

————————————————

References:

Alegria, M., Vallas, M., & Pumariega, A. (2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19(4), 759–774. 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001

Belli, B. (2020, January 30). National survey: Students’ feelings about high school are mostly negative. Yale News.

https://news.yale.edu/2020/01/30/national-survey-students-feelings-about-high-school-are-mostly-negative

Cohen, J. (2021). School safety and violence: Research and clinical understandings, trends, and improvement strategies. International journal of applied psychoanalytic studies, 18(3), 252-263.

Diliberti, M. K., Rainey, L. R., Chu, L. I. S. A., & Schwartz, H. L. (2024). Districts try with limited success to reduce chronic absenteeism. RAND.org Publications and Research Reports.

https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA900/RRA956-26/RAND_RRA956-26.pdf

USDE (2023). U.S. Department of Education. Chronic Absenteeism.

https://www.ed.gov/teaching-and-administration/supporting-students/chronic-absenteeism

Durlak, J.A., Weissberg, R.P., Dymnicki, A.B., Taylor, R.D. & Schellinger, K.B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14678624

Eklund, K., Burns, M. K., Oyen, K., DeMarchena, S., & McCollom, E. M. (2022). Addressing chronic absenteeism in schools: A meta-analysis of evidence-based interventions. School Psychology Review, 51(1), 95-111.

Kotter, J. P., & Cohen, D. S. (2012). The heart of change: Real-life stories of how people change their organizations. Harvard Business Press.

Malika, N., Granillo, C., Irani, C., Montgomery, S., & Belliard, J. C. (2021). Chronic absenteeism: Risks and protective factors among low‐income, minority children and adolescents. Journal of School Health, 91(12), 1046-1054.

Moeller, J., Brackett, M., Ivcevic, Z., & White, A. (2020, April). High school students’ feelings: Discoveries from a large national survey and an experience sampling study. Elsevier, Learning and Instruction, 66.

NAGB (2022). A Primer on Attendance and Chronic Absenteeism on the Nation’s Report Card and Beyond. The Nation’s Report Card (NAEP). National Assessment Governing Board. https://www.nagb.gov/naep/chronic-absenteeism.html

NCES (2024). Irwin, V., Cui, K., and Thompson, A. Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2023. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Institute of Educatioinal Science.

NCES (2024). Crime, Violence, Discipline, and Safety in U.S. Public Schools Findings From the School Survey on Crime and Safety: 2021–22 First Look JANUARY 2024 Riley Burr Jana Kemp Ke Wang American Institutes for Research Deanne Swan Project Officer National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2024/2024043.pdf

Northern, A. & Eggars, C. (2022). When students feel unsafe, absenteeism grows.

Thomas B. Fordham Institute. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/when-students-feel-unsafe-absenteeism-grows

OECD (2015). Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en

Shen B., McCaughtry N., Martin J., Garn A., Kulik N., & Fahlman M. (2015). The relationship between teacher burnout and student motivation. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 519–532.

Sutcher L., Darling-Hammond L., & Carver-Thomas D. (2019). Understanding teacher shortages: An analysis of teacher supply and demand in the United States. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 2 7(35), 1–40.

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting Positive Youth Development Through School-Based Social and Emotional Learning Interventions: A Meta-Analysis of Follow-Up Effects. Child Development 88(4), 1156-1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864

Van Eck, K., Johnson, S. R., Bettencourt, A., & Johnson, S. L. (2017). How school climate relates to chronic absence: A multi–level latent profile analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 61, 89-102.